“Neither Snow nor Rain…”: Growing Pains Come with A Growing Reach

This is the second article in our series on the history of the USPS. In this article, we’ll examine how Congress formally established the post office. We’ll also explore how the post office expanded alongside a growing United States and the legend of the Pony Express! Throughout this series, we’ll look at the different stages and challenges of the United States Postal Service over its 250 years of operation.

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay up to date with our USPS series, company news, and more!

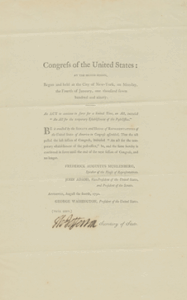

“An Act for the Temporary Establishment of the Post-Office”

Seven years after the end of the American Revolutionary War, Congress would publish a one-page document called the Post Office Act of 1790. This would allow Congress to begin building and implementing the infrastructure needed to create a nationwide postal system.

As discussed in our first article in this series, Great Britain and the American colonies had built up multiple postal systems. These revolved around loosely connecting the 13 colonies together. The innovations developed by Benjamin Franklin during his time as Postmaster General helped to form and develop a cohesive postal system.

While the new United States Congress inherited a far more organized postal system than Franklin’s, the question now was how to expand the postal system and keep it going. This question would be tackled in the Post Office Act of 1792.

This act established three important pieces of policy regarding the post office:

- Congress would control postal policy, meaning the post office would be overseen by Congress.

- Newspapers could be mailed at “extremely low rates” to help move news and information quickly through the colonies.

- Opening mail or letters for surveillance became illegal.

From now on, the post office would be called the General Post Office and would be managed by a postmaster general (with oversight from Congress).

Room for Growth

As the United States expanded throughout the 19th century, the post office grew in tandem with the country. By 1812, the post office had expanded its network of postal roads and routes by almost 47,000 miles.

During this period, the post office would rely on stage coaches, steamboats, and contractors to deliver mail to Americans across the expanding country. However, the cost to use the postal service remained high. By the 1840s, it cost roughly 20 cents to mail a letter going 150 miles or more across the country. Most paying users of the postal system were businesses. They kept in touch with suppliers and customers via mail. Most people used the mail to get their newspapers, as most local newspapers were postage-free deliveries between 1845 to 1963.

In 1845, Congress turned the post office into a public service (i.e., no longer a for-profit business for the government) and reduced the cost for mailing a letter to 5 cents (the final cost of which could vary depending on distance).

“The number of letters in the U.S. Mail more than doubled after the 1845 postage rate cuts, increasing from an estimated 24.5 million in 1843, to 62 million just six years later. In 1851, Congress cut rates even further.”

“America’s Mailing Industry: Powered by the United States Postal Service” – National Postal Museum

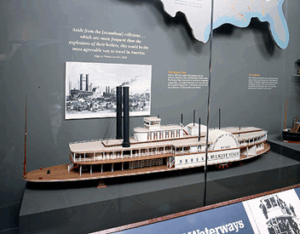

During the early 1800s until the 1860s, the expansion of the railroad system led to a significant shift in mail delivery, which heavily relied on steamboats and riverboats. In the 1820s, all steamboat routes became postal routes. These boats were, surprisingly, more reliable than most inland postal roads. This is mainly because even the most well-maintained routes were expensive, dangerous, and low in quality. By the 1850s, these floating mail routes would extend to ocean steamers that traveled between the East and West coasts. While this continental and oceanic network of ships had benefits and drawbacks, these vessels became essential communication links across the country.

The Pony Express: Speed, Risk, and a Wild Ride West

While steamboats and ships carried mail miles across vast bodies of water, overland mail delivery to California didn’t begin until 1848. At the time, inland mail routes were unreliable, slow, and difficult to improve quickly. Railroads were still decades away from forming a nationwide system, and the first transcontinental railroad wouldn’t be completed until 1869.

This was a time before highways, trucks, and modern logistics. Delivering mail across the continent could take three weeks– if you were lucky. More often, it took a full month or longer for a letter to reach the West Coast.

But where most people saw a logistical nightmare, entrepreneur William H. Russell saw an opportunity.

With the Civil War looming and fears that the Confederacy might cut off key routes between the federal government and California, Congress was desperate for faster, more reliable communication. Enter Russell’s bold idea: a high-speed horseback relay stretching nearly 2,000 miles.

Birth of the Pony Express

Russell teamed up with Alexander Majors and William B. Waddell to form Russell, Majors, and Waddell, the company behind what would become known as the Pony Express. The route ran from St. Joseph, Missouri, to San Francisco, California, and relied on a network of about 200 relay stations spaced roughly 10 miles apart.

At each station, fresh horses and riders were swapped out to keep the mail moving at top speed. Pony Express riders could cover up to 100 miles per day, switching horses every 10-15 miles.

Fun Fact: Each rider went through around 5 horses a day, riding day and night through weather, wilderness, and hostile territory.

To recruit riders for this exciting yet dangerous venture, the company famously put out this ad:

“Wanted. Young, skinny, wiry fellows not over 18. Must be expert riders willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred.”

Transportation in America’s Postal System – Rickie Longfellow (for the Federal High Administration in the U.S. Department of Transportation)

Legend Status, Short Lifespan

The first westbound Pony Express delivery arrived to cheering crowds in San Francisco on April 13, 1860. Though the service only lasted about 18 months, it left a massive mark on the history of American mail.

It was always meant to be temporary—a stopgap until the Transcontinental Telegraph was completed in 1861. Once instant communication became possible, there was no longer a need for high-speed horseback riders.

Still, the Pony Express achieved a near-legendary status. Reportedly, only one mailbag was ever lost during its entire run. When the operation shut down, it was sold to Wells Fargo, sealing its place in the mythology of the American West.

Until Next Time…

In the next article in our USPS history series, we’ll dive into the inventions and innovations that paved the way for modern mail delivery.

Don’t miss it— subscribe to our newsletter to keep learning about the fascinating story of the United States Postal Service and how it shaped the way we connect today.